Zipfov zákon je známy už dlhšie. Odolával vysvetleniu takmer jedno storočie a stal sa najväčšou záhadou výpočtovej linguistiky. Nedávno médiami prebehla správa, že s jej riešením prišiel Sander Lestrade z Radboud University of Nijmegen. V krátkom rozhovore vysvetľuje svoje riešenie Zipfovho zákona.

Rozhovor so Sanderom Lestradeom o jeho riešení storočnej záhady Zipfovho zákona

1. Môžete v krátkosti opísať Zipfov zákon našim čitateľom?

Sander Lestrade: Zipfov zákon hovorí, že frekvencia slov v texte môže byť popísaná vo vzťahu k jeho frekvenčnej pozícii, že druhé najčastejšie používané slovo je spolovice časté ako prvé (frekvencia prvého slova/2), tretie slovo má tretinovú frekvenciu frekvencie prvého slova (frekvencia prvého/3) atď. Celou cestou dolu až po posledné používané slovo, ktoré sa vyskytne iba raz!

2. Platí Zipfov zákon pre každý jazyk? Ak nie, pre ktoré jazyky neplatí?

Sander Lestrade: Hoci som to sám neskontroloval, jazykovedci tvrdia, že zákon samozrejme platí pre každý jazyk. (Povedal by som, že neplatí pre pindžin jazyky, no tie nemajú vlastnú gramatiku.)

3. Môžete nám vysvetliť Váš objav? Citujúc z tlačovej správy "Ak vynásobíme rozdiely vo význame vnútri slovného druhu (word classes)", s potrebou pre každý slovný druh (word class), nájdete úžasnú Zipfiánsku distribúciu." Môžete to vysvetliť trochu bližšie, čo je rozdiel vo význame, ako to kvantifikujete? Možno príklad pomôže.

Sander Lestrade: Viem si predstaviť, že to takto povedané znie trochu neprehľadne :) Myšlienka je, že slová sa líšia v špecifikácii významu: "auto" je všeobecnejšie než "SUV", ale viac špecifickejšie ako "vozidlo". Môžete to namodelovať v počte (abstraktne numericky) významových dimenzií, pre ktoré je slovo špecifikované. Pre čím menej rozmerov je slovo špecifikované, na tým viac odkazov môže byť v princípe použité (pre čokoľvek je niečím). Ale na to, aby bolo použité úspešne, by slovo malo byť dostatočne špecifické na vybratie jeho odkazov v kontexte (významových odkazov). Možete to simulovať generovaním kontextu s cieľovým odkazom a niekoľkými odputávacími objektmi (number of distractor objects), a potom sa pozrieť, ktoré slová sú dostatočne špecifické na určenie cieľa a náhodne vybrať jedno z nich.

Alebo môžete vypočítať pravdepodobnosť, s ktorými slovami bude použité, berúc do úvahy ich významové špecifikácie. Takto môže byť ukázané, že najčastejšie používané slová majú priemerné špecifikácie (moderate specification), ktoré sa správajú pekne kvadraticky voči frekvencii používania slov v prirodzenom jazyku (kontrolovaním korelácie medzi frekvenciou používania slov s ich pozíciou v slovných taxonomiách akým je WordNet).

Toto je hlavná časť: slová by mali byť čo sa týka významu všeobecné, aby boli zvažované často, ale dostatočne špecifické aby boli používané.

A vo výpočtových modeloch, pravdepodobnosť používania slov môže byť vypočítaná exaktne. Táto sémantická pravdepodobnosť musí byť násobená (doslovne) s potrebou slova v kategórii. Jazyky majú pravidlá, ktoré hovoria ako majú byť slová kombinované. Sloveso potrebuje jednu alebo dve nominálne frázy (frázy s podstatným menom), nominálna fráza sa vo všeobecnosti vyskytuje s členom, atď. To vedie k niekoľkým slovným druhom (ako slovesá, podstatné mená, zámená, predložky), ktoré majú očakávanú frekvenciu používania v jazyku.

Približne, druhy sú používané rovnako často, ale ohromne sa odlišujú veľkosťou (množstvom slov): v Angličtine máme len tri členy, ale desiatky tísíc podstatných mien. Dôsledkom je, že člen je používaný omnoho častejšie ako podstatné meno. Berúc do úvahy čo bolo povedané o význame, slová nie sú používané rovnako často v rámci svojich druhov. Hoci, to záleží na ich významovej špecifikácii.

4 . Dáva nám Vaše vysvetlenie-teória náhľad do toho, prečo sú jazyky postavené práve takýmto spôsobom? Prečo majú Zipfiánsku distribúciu a nie nejakú inú distribúciu?

Sander Lestrade: Berúc do úvahy, že dané slovné druhy (word classes) sa rádovo odlišujú veľkosťou, určitá veľmi hrubá mocninová závislosť je očakávateľná. Otázkou potom je, prečo majú jazyky malé gramatické a veľké lexikálne/slovné druhy (lexical classes). Slovné/lexikálne druhy sú vysvetliteľné ľahko: potrebujeme mnoho slov keď chceme hovoriť o veciach ktoré nás zaujímajú. Prečo vznikli gramatical classes je menej jasné. Podľa mňa, sú náhodným postranným produktom používania jazyka, ktorý sa vyvinul postupom času, nie sú vnútornou časťou jazyka. No nie každý by s tým súhlasil :)

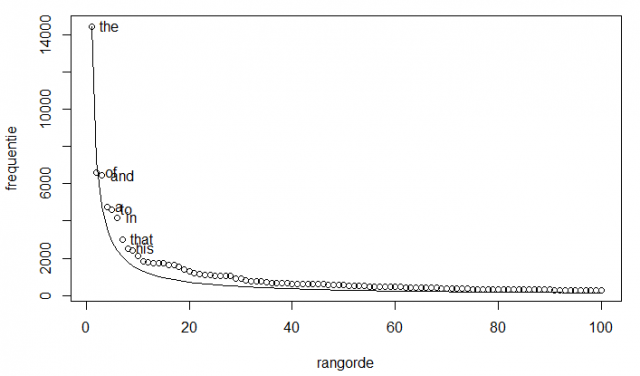

Zipfianské rozdelenie frekvencie (vertikálna Y-ová os) a poradie vo frekvenčnom stĺpci (horizontálna X-ová os), prvých sto slov Melvillového Moby Dicka. Spojitá krivka ukazuje predpoveď Zipfovým zákonom a krúžky zobrazujú skutočnú frekvenciu slov v texte.

Interview with Sander Lestrade about his solution to a century-old linguistic problem

Zipf´s Law is known for a long time. It resisted the explanation for almost a century and became the biggest mystery in computational linguistics. Recently, the media reported that Sander Lestrade from Radboud University of Nijmegen came to a solution. In a brief interview he explains his solution to the Zipf´s Law.

1. Could you, please, shortly describe Zipf's law to our readers?

Sander Lestrade: Zipf's law states that the frequency of a word in a text can be described in terms of its frequency rank such that the second most frequently used item is half as frequent as the first (frequency first item/2), the third word has one third of the frequency of the frequency of the first item (frequency first/3), etc. All the way down to the least used word that appears only once!

2. Does every language follow Zipf's law? If not, which languages do not follow Zipf's law?

Sander Lestrade: Although I haven't checked it myself, linguists say the law holds for every language indeed. (I'd predict that it does not hold for pidgin languages, however, as these do not have a proper grammar.)

3. Could you, please, explain to us your discovery? Citing from announcement "If you multiply the differences in meaning within word classes, with the need for every word class, you find a magnificent Zipfian distribution." Could you, please, explain it a bit closer, what is the difference in meaning, how do you quantify it? Maybe an example will help.

Sander Lestrade: I can imagine that this sounds a bit opaque like this;) The idea is that words differ in meaning specification: "car" is more general than "SUV" but more specific than "vehicle". You can model this in terms of a number of (abstract numerical) meaning dimensions for which words are specified. The less dimensions a word is specified for, the more referents it could apply to in principle (for anything is a "thing"). But in order to be used successfully, words have to be specific enough to single out their referents in context. You can simulate this by generating contexts with a target referent and a number of distractor objects, then see which words are specific enough to identify the target, and randomly select one of these. But you can also calculate the probability with which words will be used, given their meaning specifications.Thus, it can be shown that the most frequent words are of moderate specification, which squares nicely with the frequency of use we find for words in natural language (by checking the correlation between the frequency of use of words with their position in word taxonomies such as WordNet). This is the meaning part: words have to be general in meaning in order to be considered frequently, but specific enough to be used indeed. And in computational models, the probability of use of words can be calculated exactly.

This semantic probability should be multiplied (literally) with the need for a word of that category. Languages have rules that say how words should be combined. A verb requires one or two noun phrases (or pronouns), a noun phrase generally comes with an article, etc. This boils down to a number of word classes (such as verbs, nouns, pronouns, prepositions) that all have an expected frequency of use in a language. Roughly, the classes are used equally often, but they differ in size hugely: there are only three articles in English, but tens of thousands of nouns. A a result, an article will be used on average much more frequently than a noun.

Given what what was just said about meaning, words are not used equally frequently within their class, however. This depends on their meaning specification.

4. Does your explanation-theory tell us some insight why are languages build in this way? Why they have Zipfian distribution and not some other distribution?

Sander Lestrade: Given word classes that differ in class size by orders or magnitude, some very rough power-law like distribution could be expected. The question then is why do languages have small grammatical and huge lexical classes. The lexical classes are easily explained: we need many words to talk about the things that interest us. Why grammatical classes develop is less clear. In my thinking, they are accidental by-products of language use that only develop over time, not an inherent part of language. But not everyone would agree with this;)

lesna.vevericka

asdfasdf